Antifreeze fluid and hallucinations

It was only here that the real Sahara began. The next stretch was a daunting 1,100 kilometres, with a single supply station halfway to Tabankort. Many travellers perished in the desert, having drunk the last drop of water from their car radiator in desperation. It was a good thing that Hanuš was given two planks from an old barrel to place under his wheels when he got stuck. This way he didn’t have to deflate the tyres to increase their surface area on the ground – and then inflate them again with a manual pump in the roasting heat.

He set off on the most challenging section after thoroughly checking the car, lubricating the chassis and adjusting the brakes, with a supply of 173 litres of petrol, 25 litres of ordinary water, 3 litres of mineral water and 15 litres of oil. He was carrying 52 litres less water than the safety regulations required, but he didn’t want to overload the car. He could not drink the water from the radiator, because he was using an antifreeze additive that did not evaporate so quickly.

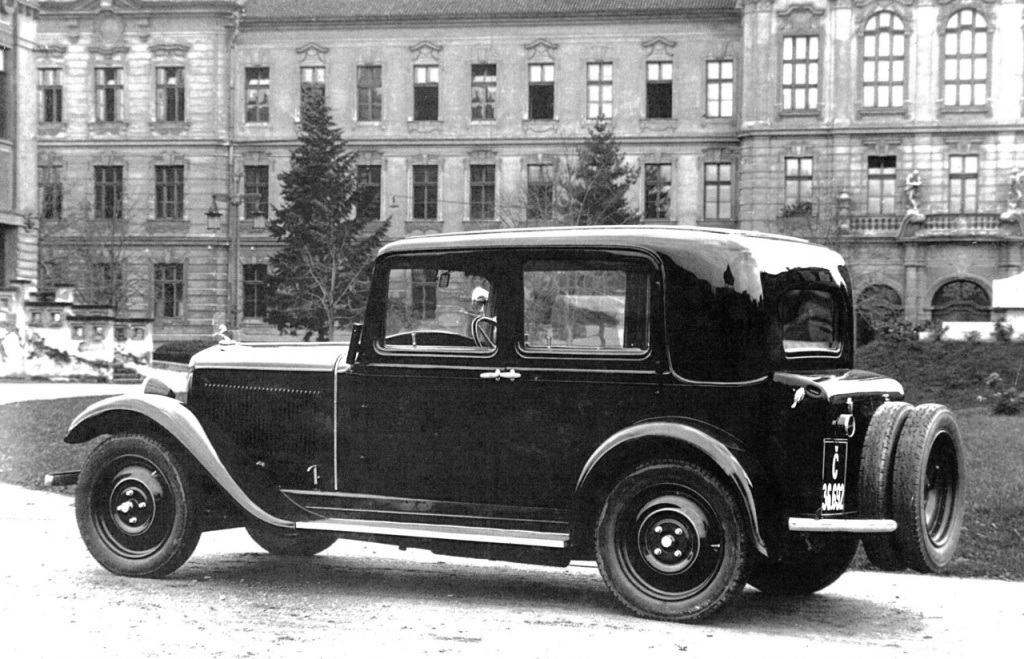

The Škoda 633’s interior had the typical simplicity of its time but was perfectly functional.

The Škoda 633’s interior had the typical simplicity of its time but was perfectly functional.

The heat and fatigue soon led to hallucinations behind the wheel: a mirage of a forest, will-o-the-wisps flying through the air. Bakik, the mute African guide who accompanied Hanuš on this part of the journey, did not know how to drive. Finally Hanuš reached the Sudanese border. “The terrain there is dreadful. The deep sand is strewn with grassy humps, filled with sand up to 30 cm high, and the grass itself often reaches the radiator. The dried-up tops of the grass fly onto the windscreen and in the glare of the lights it gives a fantastic impression of exploding sparklers,” Hanuš recalled.

With its 1.8 litre engine and 180 mm clearance, the car often inched forwards in first gear, its battered chassis and bodywork threading a route between tree stumps. Hanuš’s silent guide Bakik drank only sparingly, for he was just sitting there and not working. Via Tabankort, the explorer arrived at the settlement of Gao in French West Africa, having covered the 1,300 km from Reggan in 48 hours instead of the usual three days.

Cover of the book Crossing the Sahara in a Škoda 633, which Hanuš wrote after his return from Africa.

Cover of the book Crossing the Sahara in a Škoda 633, which Hanuš wrote after his return from Africa.